No sensible consideration can be made about music - as about any other expression of human ingenuity - if one is not clear about the relationship between the three parts of which it is composed: infrastructure, structure and superstructure.

The superstructure is what everyone perceives and is fascinated by it, or, in music, harmony.

Infrastructure is the DNA of music, the element from which everything originates, namely rhythm.

The structure is the middle world, the one in which the insiders are placed, those who compose and reproduce, with voice or instruments, music.

We can say that structure is the rationalization and abstraction of musical processes that is concretized through the formulation of the rules that govern both the infrastructure and the superstructure (as, in language, grammar and syntax govern speaking and writing, even of those who know nothing about one or the other).

The same is true, albeit with different variations, not only for language, but also for literature, architecture, fashion, the automotive industry, gastronomy....

We are born, grow up and develop in a world pervaded by sounds but we become aware of this sound environment only on a few specific occasions: when the sounds are missing (silence), when the sounds overlap with each other producing unpleasant effects (noise), when the sounds appear in a cyclical (or cadenced) way and unconsciously perceived as organized.

SILENCE IS OUT OF ORDER

Silence can be sought but it is difficult to obtain: we can contribute by being silent and firm but we cannot govern everything around us in the same way. Also because, even if we are silent and still and – perhaps – plugging our ears, we cannot prevent our body from emitting sounds (in the USA, many years ago, a group of researchers created a totally acoustically isolated room inside which absolute silence could be obtained and conducted experiments on the effects of total silence on humans. The first striking fact was that, whatever the condition of the person subjected to the experiment - sex, age, race, structure and physical or mental integrity, etc. - he could not stand immersion in absolute silence for more than a few minutes as this state induced acute pain and delirium).

Noise is the characterizing element of the environment in which we live. Up to a certain level we can live with it, put up with it, fight it.

Beyond that, we try to avoid it by implementing the most disparate techniques, ranging from escape to the creation of a bigger noise that can overwhelm the background noise (an ugly thing created by me is less ugly than the set of ugly things created by others...).

WHITE NOISE

In many children with autism the phenomenon of "white noise" has been found: they do not perceive the sounds of the surrounding environment as if they were totally deaf (and for this reason they have great difficulty learning to speak) but they perceive all the sounds inside their body (heartbeat, blood flow, flows of the lymphatic system, breathing, outflow of substances into the digestive system, tensions of the muscular system, friction of the skeletal system...) that overlap creating a "noise" that in particular stress conditions becomes unbearable.

In these extreme cases, children are found to be able to carry out apparent self-harm: they grasp any object and begin to hit their body, mainly the head, with it.

In reality, it is not a question of self-harm (even if these acts often cause injuries) but of the attempt to

counteract white noise by introducing a new, more intense and overpowering noise into the body, which is clearly distinguished from the auditory chaos produced by their body, that is: a rhythmic,

cadenced noise, which compared to the sum of the others can be perceived as one's own and, therefore,

acceptable.

Rhythm, therefore, can be defined as an organized form of noise and, for this reason, we perceive it positively, interacting with it both

unconsciously and consciously: we can involuntarily adapt our breathing, our heartbeat and our muscle movements to the rhythm, but we can also voluntarily make gestures or exercise activities

that synchronize with them, such as dancing. In extreme cases, the rhythm can lead to a state of exaltation or obsession.

Our memory retains the sensation of unpleasantness of noise and does not offer us, in a deferred time, mnemonic tools to reproduce it.

Of the rhythm, on the other hand, we are able to store type, frequencies, variants and we are able to reproduce it both slavishly and by introducing elements of personalization and adaptation to places and events. And when I say "we are capable of," I mean that primitive man - as well as many animals "was capable of.

FROM THE STREETS TO THE PARTY HALLS

OF THE PATRICIAN PALACES

Almost always, when we are faced with any human expression, whether in the cultural, scientific, legal, technical, organizational, etc., etc., fields, we take the premises from how the thing is or presents itself in its current state, or from how official sources have told us about it.

So, in our imagination, we place music in auditoriums, stadiums, cinemas, discos and dance halls, in the headphones with which we carry it with us, on Youtube, on the car radio... And if we go back in time we see it in the opera houses of the 19th century, in the baroque ones of the 17thth and 18th centuries, in the residences of the nobles and the powerful, in the churches, in the banquets of the Roman emperors and so on. But, the further we move away from today, the more the number of people who could delight in music is reduced, up to percentages that, realistically, do not exceed 1%.

The flaw in history that they teach us is that it is only the history of those who rule, of those who manage power, of those who hold the fate of others in their hands: it is only the history of the elites.

Until the beginning of the 19th century, music was not part of people's lives except on rare and cyclical occasions: sometimes a year when there was a village festival (the harvest, the grape harvest, the feast of the patron Saint of the village) and weekly, in the Christian area, when people went to church. In everyday life there was no music but there was rhythm, sometimes so evolved as to push itself to forms that could presage music.

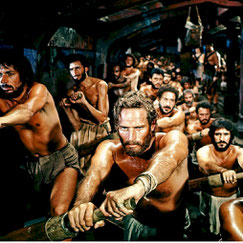

WHEN THE ONLY MUSIC WAS THE RHYTHM OF THE ROVERS

The rhythm was certainly there on board the Roman triremes and galleys, with a

percussionist who dictated the cadence of the oars on the drum, with variations imposed by the need to support or contrast the state of the sea.

And, often, the rhythm of the percussion was accompanied (seconded) by the voices of the rowers (we still hear them today if leaning against the parapet of a bridge

we linger to observe the training of the rowers, especially those with the coxswain).

And we find the rhythm that accompanies the armies of every millennium, from the Egyptians to the American Confederates. First with the domination of percussion and then with the introduction of trumpets, to guide marches, assaults, and retreats.

Rhythm desired by generals but very often also created by the soldiers themselves: all military songs, even recent ones, are nothing more than chants dominated by rhythm and certainly not by harmony. For millennia, rhythm has accompanied (and fostered) repetitive work, in the fields as well as in factories.

The rhythms were marked by the rice weeders, the reapers, the hoes, the spinning mill workers, the seamstresses, the washerwomen.

In essence, the vast world of popular music is nothing more than the re-proposition, dilated in time, of the evolutionary process from rhythm to harmony that took place in much shorter times in

the music that accompanied the powerful and the elite.

And shows one of its peaks in the American Rythm & Blues, born in the cotton plantations and which has been able to develop to reach the peaks that are attributed to it thanks to some contingent factors: the workers in the cotton plantations were millions, they operated in a market made up of tens and tens of millions of consumers,

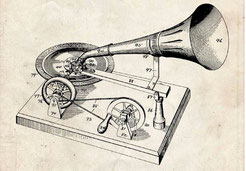

The birth and evolution of their music was parallel to the birth and evolution of its mechanical reproducibility.

GREEK THEATRE, A PRECURSOR OF TIMES AND RHYTHMS

To be honest, the statement "there was no music in daily life" is incorrect. There was a period, over two thousand years ago, when music was part of daily life (or, at least, weekly): it was a component of the theatrical performances of ancient Grecia.Il theater, however, within Greek civilization, it was not an entertainment activity but a system, well planned and implemented, of education and civic acculturation (proof of this is the large number of theaters built even in the smallest urban agglomerations, a practice followed, with the same purposes, by the Romans up to the threshold of Imperial Rome).

Aristotle, in the book Poetics, clearly explains the function of the "arts" (the main ones are tragedy, comedy and farce), aimed at defining the roles (and the control over the roles by the people) of those who hold power, of those who constitute the backbone of society and of those who are on the margins.

In the list of "arts", Aristotle does not list music but mentions it several times, attributing to it a fundamental role in underlining, emphasizing or dramatizing the various situations. In short, a secondary, important but, fundamentally, "service" art.

Another area in which music has entered people's daily life (more correctly: weekly) is the church (understood as an architectural artifact used to bring people together).

And this dates from the late Middle Ages onwards. The great intuition of the popes and the clergy was to make people find some basic things that were not there outside. In this case: images, scents and music.

Until then, images only adorned the walls of the houses of the powerful and their function was to "impress" their peers, offer allure, credibility and charm to those who showed them. In fact, the subjects were the ancestors, the illustration of some deeds – mostly warlike – of the current or remote members of the family, visions of the possessions.

The Church (understood as an institution) had the great intuition to tell about

itself, the principles on which it was based, the spiritual objectives it pursued. And to tell them with images because they had to be usable by an endless audience of illiterates. And to be more

incisive, they entrusted the creation of these images to the best illustrators of the time (later called "artists"), with extraordinary results.

A further element that hovered in the streets of villages and cities at that time was the stench, mainly of urine, shit, sweat and decomposing organic

substances.

Another great intuition of the Catholic Church was to create an environment within places of worship in which that dominant stench was not present but, on the contrary, opposed to that stench.

Hence the massive use of aromatic substances on which, among all, incense predominated, strong, penetrating and capable of impregnating even clothes and, therefore, of being dragged out of the church and, for a short time, opposing and counteracting the external stench that dominated.

THEN IT HAPPENED THAT THE PROFANE BECAME SACRED

Finally, music. Outside the places of worship, the noise and rhythms that marked work and military activities dominated. No trace of harmony and/or melody.

Let's imagine what effect it could have on people immersed in this sonic hell, now confused and now organized (but when it was organized it accompanied only fatigue and battle), to be immersed in a harmonious, captivating and penetrating sound environment as penetrating as a music originating from the pipes of an organ and a song gushing not from a single voice but from a choir can be.

And, even in this context, they had the intelligence to entrust the creation of this music to the most sublime minds in circulation in all times of their glorious centuries.

This was the function of music until the mid-nineteenth century, that is, until technology allowed its mechanical reproduction, free from the context for which it was composed and performed. It is only thanks to that contingency that music began to be enjoyed for its own sake, transporting it from the radio, magnetic tape and record to designated places such as auditoriums and concert halls (open to all), which did not exist before.

The fact remains, however, that for many more decades (over a century) music has remained an art of "service": in opera (from Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to Giuseppe Verdi and beyond), in musicals, in cinematography, in dance halls. The changes induced by technological innovation, however, are not always and only consequential.

The changes in the demands that prompted commissioning and composing music go back much further than the invention of the record and the radio and are located in a totally different area.

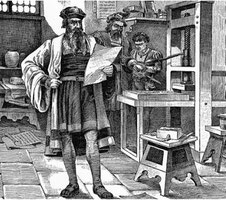

The technological event that conditioned all the arts (and with them, music) for the following centuries dates back to 1455, the year in which Johannes Gutenberg, assembling different technologies, all pre-existing, was able to produce "even" 180 copies of the Holy Bible.

THE PRINTING PRESS:

THE INVENTION THAT UNDERMINES A SYSTEM OF POWER

Until then, all copies of the Bible in circulation were copies made by hand by religious called, in fact, scribes. Rare and very precious tomes that ended up in the hands of the Pope, cardinals, bishops and abbots of the most prestigious and influential cathedrals and convents. Their diffusion was conditioned by the same process of lowering clothes into poor families: the jacket of the older brother passed to the younger one, and then to the next, until the sixth or seventh child had a worn, discolored, felted garment.

To the parish priests of the suburban and rural churches, when it arrived, the Bible appeared worn out and often almost illegible.

Hence it became necessary to support the communication of the "word" with tools of more immediate use, such as the paintings on the walls of the churches (a sort of comic edition of the Holy Scriptures), the sculptures, the bas-reliefs, the words of the officiating prelate. In short, what is called the "Oral Tradition".

The spread of the printed Bible, which cascaded in Northern Europe after the first edition edited by Gutenberg, generated a series of side effects: having something to read (and something that, by reading it, can lead you to the salvation of the soul) produced a great stimulus to learn to read.

Once people learned to read, realized that what the prelate officiating at Holy Mass usually told corresponded minimally to what was written in the Gospels and in the Old Testament. This set in motion – again in Northern Europe – a movement of contestation of the Church of Rome that focused on two main themes: the denunciation of the market of indulgences (a topic of strong popular appeal: follow the money...) and the claim of the supremacy of the Sacred Scriptures over the Oral Tradition (still one of the cornerstones of the Catholic Church).

The main actor in this protest was Martin Luther, who was born 27 years after the first printing of the Bible and died 91 years later. With some simplifications, we can say that the technological innovation introduced by the press and Gutenberg's movable type is at the origin of the birth of Protestantism. And this has led to significant consequences, under everyone's eyes but detected by almost no one.

The increasing passing of printed Bibles from hand to hand has greatly reduced the need to explain the same things through painting and sculpture:

While the churches of Southern Europe continue to be built with large availability of walls to contain the illustration of the salient moments of the Holy Scriptures, in Gothic architecture the spaces for this function are enormously reduced and pictorial and sculptural interventions are limited to iconic images, who is entrusted with the task of underlining or enhancing concepts, not explaining them: all the art of Northern Europe from the 1500s onwards is converted from the production of didactic images to that of symbolic images.

THE CONFLICT BETWEEN

WORD HEARD, WORD READ AND WORD SUNG

Since borders exist only in the minds of politicians (to defend them) and dictators (to break them), this radical change – albeit very slowly – has shifted from North to South, having a huge impact on the commissions of religious institutions to painters and sculptors.

Why explain the life and miracles of Christ with expensive images through the work of eminent painters, when the same information can be disseminated with a much cheaper printed book?

And, in order not to disperse the attention of the illiterate, who constituted the great majority of the faithful, the production of illustrated editions was started in which the art of the engravers gradually took the place, undermining it, of that of the painters.

This led to the weakening of one of the three pillars on which the appeal of the Christian religious function was based and inevitably dragged with it – albeit more slowly – the second: music.

If we analyze the mass secularly, it is nothing more than a theatrical representation in which the classic elements of tragedy dominate: the story (with a tragic epilogue and consequent redemption), the scenography and the sound commentary.

The story could not be touched, the scenography had been created by the most eminent architects, painters and sculptors (and could not be touched), the music had been composed by the greatest composers in existence (and even that could not be touched).

This led to a sad dragging of the religious function while the new generation of artists and musicians were hired by the new protagonists of Western society: the nobles, the men in charge and the entertainment impresarios.

So those skilled in the visual arts put themselves at the service of the new power and the best musicians were called upon to support the secular stories told in the baroque theaters (for a small elite), the 18th century (for a nascent bourgeoisie) and the 19th century (for a bourgeoisie now consolidated as the backbone of the new society).

Then, in the 19th century, a new fruit of technological innovation spread and joined theatrical entertainment, until it undermined it: more and more people learned to read and, consequently, poured into reading novels and short stories.

Writing, in essence, is nothing more than the graphic translation of a voice, a translation that through some graphic expedients (punctuation, italics, bold, newlines, etc.) also manages to evoke a certain amount of tones and rhythms of the voice. The reader's mind is entrusted with the function of mentally constructing (and associating) the scenography, appearance and clothing of the characters.

The 19th-century counterpart of the novel is melodrama: a sort of Broadway musical, always with strong tones, in which music is called upon to support the story represented (it is worth remembering that the counterpart of the producers of melodrama – I quote Casa Ricordi for all the others – after the producer had decided to represent a certain story, he thought about who to entrust the musical part to. And with the utmost indifference, if Giuseppe Verdi was not available, they turned to Gioacchino Rossini or Pietro Mascagni. Exactly as it happens today for film soundtracks).

The popular impact of melodrama was enormous, but with limitations: people attended it only once and had no tools to memorize the entire opera: what "passed" were a few short pieces (the so-called "arias" or "romances"), catchy and with significant content.

In short, while the "Opera" was celebrated in the theaters, in the houses and in the streets "pills of Opera" were celebrated, small pieces few minutes long, repeated to the point of obsession.

THE EPOCHAL EARTHQUAKE UNLEASHED BY

RADIO, RECORDS AND MOVIES

Until, at the end of the century, the radio and the record took over, and melodrama aligned, in fruition, with the novel: the new technical medium transmitted voice and music and the user, through the mechanisms of his mind, added scenography, costumes and physiognomy of the protagonists.

Obviously, this determined an apparent primacy of music which, stripped of the environmental and scenographic context, became the absolute protagonist, worthy of being listened to in itself, regardless of the reasons and functions for which it had been composed.

And it raised the legion of "music lovers" who did not want to know about the story for which it was composed, be it Aida, Il Trovatore or La Cavalleria Rusticana: rejoicing in the part and rejecting the whole.

Then, at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, came the movie theater which, in its first version, and for a few decades, was "silent". Soon the impresarios realized that cinema, an extraordinary and fascinating show, as it was silent did not have a strong grip on the public and could hardly compete with the theater.

And they ran for cover by associating the projection with the performance of a pianist (originally an organist) who had the function of underlining, emphasizing and tragicizing the scenes, softening the scenes, preceding their meaning, commenting on them as soon as they were completed.

Only one musician was used because improvisation was the rule and it would have been impossible to find even a small orchestra in which the individual elements could not conflict. In the transition to sound it was inevitable that music took on an important role in the architecture of the movie, so decisive that the "great" music that was able to express the 20th century is all movie music, soundtracks in the absence of which hundreds of movies would collapse miserably (just try to see Sergio Leone's first movies without a soundtrack to realize their narrative and emotional poverty).

While movie theater grew and evolved, the spread of radio and records were the occasion for the birth of a new musical product: the songs. Consciously or casually, they are nothing more than the continuation of the "pill" effect of melodrama.

If in the face of three hours of performance people ended up remembering and humming only small pieces, why not offer them a pre-packaged product, tailored to human memory, within which there were, concentrated in a few minutes, all the key elements of melodrama? That is: love, joy, dreams, betrayal, pain, revenge, etc. etc. It is enough to analyze the content of all the pop music of the last century to realize that it is nothing more than an infinite succession of melodramas concentrated in three minutes.

Until then we get to the video clips and music broadcast through web channels where, once again, the performers find themselves in the condition of adding a scenography, stage costumes, a characterizing personal look to the music sung and played.

Elements that prove to be decisive in the success of any singer or musical group of the last forty years (and it is enough to look at the latest editions of the Sanremo Music Festival, the Eurovision Song Contest or the Grammy Awards to realize this).

Here, then, at the halfway point of the third millennium, music takes a big step back to its origins and returns to being an art of service, support for the fulfillment and – sometimes – the exaltation of other arts.

It returns to being a "soundtrack", to the point that, again thanks to new technologies, today billions of people perpetually go around with a pair of headphones on their ears, transforming music from a musical commentary of invented events into the soundtrack of their lives.

RuvidaMente

RuvidaMente