"Culture" is a shopping cart full of every good thing.

"Knowledge" is a table laden with dishes made

by cooking every good thing.

Far from wanting to ape the aphoristic ability of Charles-Louis de Montesquieu or Oscar Wilde, this definition comes from a feeling experienced while visiting, in recent months, some of the most important museums in the world

where, invariably, one finds oneself grouped in wandering masses from one room to another that proceed without a logical and, often, not even spatially programmed direction. sinking their eyes into admirable works, mostly piled up haphazardly on the walls (even if there is a logic, it is a logic that satisfies those who have put

them there, certainly not those who go to see them), with the only help of small plaques or sheets of paper of the maximum size of an A4 that show, in most cases, the name of the author, the title (if it has a title) and the year in which the work was made. Sometimes (but it is rare) the place where it was exhibited and

(almost never) for whom and why. If it is portraits, the name of the person portrayed appears but, frequently, it gets away with a hasty "Portrait of a commoner", "Portrait of a girl", "Portrait

of a young gentleman".

One has the feeling that museum curators all agree in focusing solely and solely on the "Stendhal syndrome" effect, as if that magma of visitors moved compactly to

the cry of "torment me but satiate me with beauty".

It was like this in the 60s, it was still like this in the 80s when the first electronic instruments appeared in the world. And then, again, nothing changed when the world appeared on the Web and, gradually, until today that we live totally immersed in digital technologies.

And to think that the application of digital techniques (ICT / Information

Communication Technology, Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality, Artificial Intelligence) would not only be useful for the

purpose of remote use of museum assets, but would also make it possible to optimize the real use of the museum or archaeological site. And this is because - it is disheartening to point out -

most museums (Italian and otherwise) transform anyone who enters them, able, disabled or differently abled, into "inable", into an awkward, disoriented person, impaired in his ability to

understand, know, know.

To investigate the reasons for this visitor malaise, we must start with two simple questions: who makes museums? And for whom does it make them?

In most cases, those who "make" museums do them for those who commissioned them and not for those who

will visit them. And this is in contradiction with a constant of our time, namely the fact that, to visit them, often - in truth, always - you pay a ticket.

This act transforms the museum: the moment I pay to enter, that museum is something different, very different from the intentions of those who conceived it. At that moment the museum is

transformed into a product, a horrendous word perhaps, but clear and inevitable. When I pay, the payment object is transformed into a product and has to perform new functions. Even if it is a

museum, it must strip itself of its cultural arrogance and ask itself the problem of satisfying those who buy this product.

Assiduously observing the endless queues of tourists who try to access the Vatican Museums in Rome, the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, the Louvre in Paris or the MET in New York every day, one wonders if anyone has taken the trouble to order them with them in mind. Or, at least, for some of them. Of course he cannot have designed them for everyone, because in those long queues there are people of all cultures, of all ages, of all languages.

THE THREE FACES OF THE VISITOR

If we try to understand and catalog this type of visitor (and, of course, all visitors to museums and archaeological sites), we can broadly identify three categories.

The first is that of the bearers of listening, i.e. those people who enter a museum by convention: because, when you visit a tourist destination "you must" also go and visit the museums. In their city they would never enter a museum but then change cities and go there.

Most people who cross the threshold of a museum or an archaeological site belong to this category. And

they are people willing to listen: they go through a door and have no precise or defined routes and are generally attracted in the first instance by generalist museums, that is, by those that

offer a little bit of everything.

For an insider, probably, hearing that the Capitoline Museums in Rome are a generalist museum will seem like blasphemy, but the substance is that: there is painting, there is

sculpture, there is the nineteenth century, there is Roman history, there are the Etruscans, etc. etc. And this is the classic museum of the bearer of listening, that is, a visitor ready to

receive but not to communicate, to react, to interact. This does not mean that his level of attention or that his predisposition to attention is

lower, but it is an exclusively receptive attention.

THE BEARERS OF NEEDS

The second category is that of those with needs. They are those visitors who enter a museum by elaborating precise routes, who have needs and try to satisfy them through a visit to a museum.

They are ready to receive by searching, so they are not passive (i.e., they are not compressible in the

relationship "what you give me I receive") but they go looking for information and answers.

They are ready to receive but they are not yet ready to communicate, to interact, that is, to provide feedback. However, they have an extreme level of attention and focused on objectives,

specific and targeted. This is a category that frequents other types of museums, places where it finds a specialization, temporal or thematic. And there they think (or delude themselves) that

they will find satisfaction for their needs.

THE BEARERS OF QUESTIONS

The third category, which represents a very small portion of visitors, are the questioners. They are the most advanced visitors, they use or, rather, would like to use, the museum by continuously crossing elements of vertical and horizontal interest. They invert the trend of their information tracks in an alternation of inputs and outputs, in the sense that they receive and, once they have received and processed the data, they would like to return inputs to the object, to the place in which they are immersed, and then have other answers that can also come from other sources.

In short, they dynamically broaden and narrow the answers obtained and then reuse them as the source of

new research and interests. From each answer they develop new paths, precisely because they are bearers of questions: so they are not satisfied with the flow of information that comes to them

through what is exhibited in the museum.

They have a very high level of attention, of a professional type, which has its peaks on the occasion of solicitations: every time the museum provides them with

solicitations, their attention grows.

VISITOR AND/OR CONSUMER?

The application of ICT techniques (what for convenience we call "virtual") in a museum or archaeological site, should be the element that infuses vital value to what is on display, that is, that allows any piece of that museum to be "right" for these three types of visitors, and therefore to give satisfaction to each of the categories identified. First of all as consumers, that is, people who bought that product because for better or worse there was a price to pay and they paid that price.

Satisfying their requests enriches with interest a museum situation that may be objectively of the highest interest but only for insiders, for scholars, but it cannot be, if there are no such applications, for a viewer who is part of the two other categories.

Now, to achieve this result we must carry out interventions that must first of all respect the place, must respect the find, respect what is exhibited and must not force it to be something other than what it is, because, otherwise, we betray the product, because those who paid did so to visit a museum and not the virtual representation of a museum.

The virtual representation of the museum or the object on display there must serve to give him more, to give him answers to those questions that were latent in him at the time he paid for the ticket and that materialize during the visit.

If we disregard our cultural background and that of specialists, any object exhibited in a museum, in essence, is a trivial matter. The most precious Etruscan amphora, from a commodity point of view, is an almost insignificant object. It becomes of great value when compared to the place and time in which it was created and used.

It takes on meaning if it is transformed from an object into a sort of freeze-frame, the junction of a history in the making towards which all the before converges and from which all the after unfolds. If there is no before, if there is no after, that vase, the most beautiful vase there is, remains a vase, perhaps well decorated, with an attractive shape, but nothing more than a vase. If we disregard the before and after, it is nothing. Or it is little.

It follows that any element we introduce into the museum itinerary, whether it is an element of virtual reality or simply a sign, a caption, an audio guide, a sequence of slides, must have the function of placing each exhibit (or set of exhibits) at the center of an information flow that enhances it as the point of arrival of an evolutionary process. a deposit of testimonies and information on the state of the art of the theme in which it is placed and a starting point for understanding the evolutionary process that follows

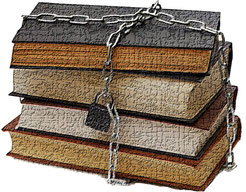

FROM A CLOSED BOOK TO AN OPEN BOOK

We must do all this by preparing non-invasive interventions, which respect the objectivity of the works on display and which do not oblige you to use them anyway. Because the visitor is never rigidly inserted into one of the three conditions we have described above.

Even those who begin the visit as bearers of questions, regarding certain topics can become bearers of listening. And so we must not force him to follow certain paths: we must simply offer him the opportunity to deepen certain topics, and according to the itinerary most congenial to him.

Obviously, the guiding concept of respect must not prevent the museum from implementing techniques that stimulate interest in learning (solicit, not "force"), towards the broadening of the horizons of personal knowledge. Although guided and assisted, the visit to the museum must be satisfactory but does not have the obligation to be exhaustive of the potential interests of the visitor, and of all the topics that can be proposed upstream and downstream of what he will see.

To understand what the potential of digital technologies is, from this point of view, it is sufficient to compare them with the traditional tool for transmitting knowledge to which we are all accustomed: the book. The great difference between the book and multimedia supports is volume, materiality (it is no coincidence that the words "book" and "volume" are synonymous, perfectly interchangeable).

The more bits of information there are concentrated in a book, the more unapproachable it is. We gladly leaf through a 200-page book, but in front of a 1000-page volume we begin to have some reluctance. If it has 2000 we tend not to open it.

The growing number of pages holds us back, induces in us the idea of fatigue, of bewilderment, of inadequacy in the face of the commitment required.

The beauty of electronic media (from CDs to DVDs, to websites) is that they do not make us perceive the thickness: they place us in front of a single page, always perfectly within the reach of our potential commitment, whatever it may be, and the decision to delve into the "thickness" is always only ours and never conditioned by the number of pages behind the one we are consulting, quantity that exists but whose magnitude we cannot perceive.

The lack of perception of "depth" makes us more casual, agile, available: it allows us to go anywhere

without prejudices of a cultural, operational, logistical, temporal nature. It prevents our "glance" from making an estimate of how much time (and effort) it will take to satisfy our contingent

interest.

When the multimedia support is well conceived, we spend much more time on it than we would have estimated in advance because we enter a path that stimulates our

interest to proceed, page after page, link after link, gratified by the fact that the answer to our questions is always at hand and we do not have to look for it among a thousand pages.

FROM COMPULSORY ROUTES TO OPEN ROUTES

To the lack of "thickness", then, is added the non-rigidity of the paths. Faced with any find, each of us is stimulated to interests of a different nature that can be satisfied by entering into vertical or horizontal paths of knowledge. To better understand the meaning and value of the object displayed on a bulletin board, we may be interested in knowing the before and after. Or, horizontally, we want to compare it with similar and contemporary finds from other areas (the vases of Cerveteri and those of Tarquinia, the Greek ones and those used on the banks of the Nile). But we can also be interested in an in-depth knowledge, how that find was produced, marketed, used.

In the face of this type of request, the book proves to be rigid, not very functional; it forces us to

find answers by following its pre-established paths, it makes us lose time, momentum, enthusiasm.

Computer support, on the other hand, can save us time and increase our momentum and enthusiasm. It adapts to our needs, it allows us to change our minds: we can investigate vertically and then explore horizontally and at any time begin to dig deep and then, perhaps, from any point, resume our path vertically or horizontally.

These infinite

possibilities for in-depth study and their total adaptability to the status of any visitor must convince us that the image usually associated with the expression "virtual museum", i.e. a room or a

station in which we can witness the reconstruction of a given "world", must be overcome and extended. It certainly must not be eliminated because its function is fundamental especially in relation to

the "bearers of listening", who represent the majority of museum visitors, visitors who need to be guided by the hand and are well prepared to receive.

But the same technology must be used to meet the needs of the most advanced visitors, those who are able to build paths of personal investigation and can decide at

any time to reverse them or direct them differently.

FROM CONTAINER TO ENGINE OF CULTURE

Only if it manages to equip itself with tools capable of responding to these needs, can the museum transform itself from a "container of culture" into an "engine of culture".

The possibility of delving into paths of knowledge that are both agile and exhaustive will transform the visitor into a culturally enriched person, who once back home will not limit himself to exclaiming "I saw a beautiful vase", but will be able to tell, through that vase, a fragment of history and human experience.

Above all, however, he will know something more about himself, about the civilization in which he is immersed and of which he is an expression. Because, what is the point of representing the past in the best way if not to understand the present, to understand ourselves?

Being an "engine of culture" means providing tools for improvement to those who live and act in that

culture.

If we don't come out better, a visit to a museum (and the museum itself) is absolutely useless.

RuvidaMente

RuvidaMente