The tomato can now be considered a typically Italian food, although it is grown and widely consumed in other countries. On the other hand, the potato, once it had crossed the Atlantic and initial diffidence had been overcome, assumed a European dimension and now plays important roles in many countries’ cuisines. However, the Italians can claim to have introduced the tuber into their gastronomy in the most creative ways, transforming it while integrating it with other ingredients to found a family of extraordinary preparations, ranging from gnocchi to crocchette (croquettes), tortini (thick, flat omelets) and sformati (molded dishes).

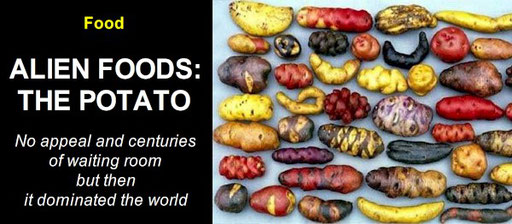

The potato originated in the Andes Mountains and was domesticated by the native peoples who were adept at growing crops at high altitudes, building terraces and using irrigation as part of their farming techniques. The potato formed the base of the diets of the peoples of Peru and Chile.

The potato was not one of the foods discovered and taken back to Europe by Christopher Columbus—he encountered only the yam or sweet potato. The regular potato came to the attention of the Conquistadores in Peru and was taken by them to Mexico. It was later transported to North America to what became the colony and state of Virginia.

The first authentic scientific description of the potato has been credited to the Dutch

botanist Charles de L’écluse, who is better known by the name

Clusius. While he was residing in Vienna in 1588, he received two tubers from the governor of Mons in what is today Belgium. The gift was accompanied by a watercolor, which was the first official

drawing of the potato. It is now part of the collection of the Plantin Museum of Antwerp. Clusius tasted the tubers and found that they had an agreeable flavor that was close to the taste of

turnips.

He wrote up a detailed description that was published in the Raziorum Plantorum Historia.

In the second half of the 16th century, potatoes were shipped to the Lowlands to supply the Flemish garrisons of King Philip II of Spain. The plant quickly spread through the Netherlands and the Rhineland.

The tubers were also listed in 1573 among the provisions of the Sangre Hospital in Seville. They were used to supplement the diets of the ailing poor and a painting of St. James, executed by Bartolomè Esteban Murillo in 1645, shows the saint distributing potatoes to the famished.

In Ireland, the potato resolved severe dietary problems but it also provoked a substantial

increase in the population, which led many to remark that the tuber must be a powerful aphrodisiac.

In 1845, the potato crop failed because of a blight and a severe famine ensued, not only in Ireland but also in other parts of Europe. Hundreds of thousands of people were forced to emigrate to the New World, North America in particular.

Irish immigrants inundated New York City, which owed much of its growth in the 19th century to the potato or, more precisely, the blight that devastated its tubers.

In 1771, a contest aimed at identifying a food that could replace cereals in the everyday diet was announced in France. The military pharmacist and agronomist Augustin Parmentier (1737-1813) won the prize by suggesting the pomme de terre (earth apple or potato). During the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), he had been held a prisoner by the Prussians, an experience that allowed him to attest—he was the first Frenchmen to do so—to the dietary virtues of the potato. Frederick II the Great of Prussia had succeeded in introducing Kartoffeln , admittedly in autocratic fashion, among the rations of his troops and, consequently, of his army’s prisoners.

Louis XVI of France enthusiastically supported Parmentier’s experiments, putting at his disposal the royal botanical gardens. The king also took to wearing a waistcoat decorated with the attractive bluish-white flower of the potato. However, the plant was viewed with suspicion by superstitious peasants, as it had been by their brethren in other countries throughout the 17th and the greater part of the 18th centuries. In the countryside, the potato was widely regarded as a source of epidemics of serious diseases like scrofula and leprosy.

The French Revolution definitively established the potato as an important element of the

daily diet. Parmentier continued to play a leading role in that process. His services in that worthy cause saved him from the guillotine and he went on to suggest some ways in which the tuber

could be prepared for consumption, mostly in soups and as a garnish. He repeatedly urged that potato starch be used instead of wheat or other cereal flours in making bread but the results were

not widely appreciated.

However, his name is inseparably linked to a classic recipe, soupe Parmentier, a potage or puréed soup made from potatoes, leeks, fresh cream, chervil, salt and pepper. La Cuisinière Républicaine, published in Paris in 1795, contained a recipe that clearly suited a time of turmoil and widespread hunger: Pommes de terre à l’économique, which was a sort of potato ball made with chopped meat, parsley and onion.

A few years later, one of the greatest cooks of all time, Antoine Carême (1784-1833), included in the category of haute cuisine such dishes as potatoes with vanilla and delicious potato croquettes.

The potato also meant a great deal to Napoleon Bonaparte. He would not have been able to shift military units and whole armies across the face of Europe as speedily as he did—rapidity of movement was a key factor in his campaigns—without the tuber. Along with the troops went enormous quantities of potatoes, which were much less costly, less prone to deterioration and much easier to process and prepare for consumption than wheat flour.

The English and Irish introduced the potato into their daily diet in a much more direct way. In 1587, Sir Francis Drake (1514-1595), who had once been a buccaneer in the Caribbean, sailed to Cartagena in what is now Colombia in the service of Queen Elizabeth II. There, he loaded potatoes aboard his ship and headed for Virginia, where English colonists were starving. By the time he arrived, the colonists had had enough, so Sir Francis took the survivors aboard and conveyed them, and the potatoes as well, to England.

It is probable that not all of the potatoes were consumed in the voyage and that some remained to be seen and, apparently, tasted by John Gerard, a naturalist-botanist, who described the tuber in his famous Herball, published in 1597.

Sir Francis’s mercy mission to Virginia created some confusion as to the origin of the potato. For about two centuries, or until 1930, it was widely believed, and not just in England, that the tuber originated in Virginia, the first English colony, which was named for Elizabeth I of England.

The plant arrived in Italy around 1560 but appeared to have been appreciated only as an ornamental plant.

Toward the end of the 17th century, Italians were calling it a truffle and, at the same time, feeding it to hogs.

It was not just the Italians who believed that the potato was related or linked to the truffle. That was a common view of people throughout Europe. In addition to calling them truffes rouges and tartuffi, people in France and Italy attributed potatoes the same powers as a stimulant and aphrodisiac as those claimed for what Italians referred to variously as tartufoli, tartufali or tartufle. Those terms were the source of the German name for the potato, Kartoffel.

The practice of cultivating the potato began to spread in Italy toward the end of the 18th century and precisely in those areas that had been affected by the Napoleonic campaigns. Still, La Cuciniera Piemontese, published in 1798, and later Il Cuoco Piemontese, which appeared in 1815, made no reference to potatoes or recipes for preparing them.

In 1816, litterateur Cesare Arici (1782-1836) published one of his best known works at Brescia, La Pastorizia, in which he observed: “Here is the potato, the elect, Ceres [goddess of agriculture] applauds it and the many uses to which it is adapted.”

However, Arici’s potato was, in his opinion, more suited to consumption by animals than by humans. For it coated the flanks of sheep with a rich layer of flesh and assured a denser flow of milk from their “turgid paps.”

However, Celestinian monk Vincenzo Corrado had already written a “Treatise on Potatoes,” which he added to the fifth edition of his Il Cuoco Galante, published in 1801, and which contained a substantial list of preparations, including potato mush, (similar to polenta), creamed potatoes and potatoes in polpette (balls), in bignè (fritters), roasted and stuffed with butter.

The document also contained the prototype recipe of potato gnocchi: “Bake the potatoes in the oven and scoop out the pulp, which should be pounded [in the mortar] along with a fourth of its bulk of hard-boiled egg yolks and with as much veal fat and ricotta cheese. Add several beaten eggs to bind the mixture. Season with spices and divide the mixture into small pieces half a finger long and as thick. Dredge the pieces in flour and boil over high heat for a short time. Sprinkle cheese over the dish and serve with meat sauce.”

The modern recipe for potato gnocchi is much simpler and probably originated in Piedmont. However, the dish also appeared in Liguria, where it yielded outstanding results, after the two regions were amalgamated into a single kingdom in 1815 under the terms of the Treaty of Vienna.

It appears in two Genoese cookbooks, along with a recipe for a purée, still known as patate machees, which was flavored “with a battuto of garlic [or pesto] and Parmesan cheese.”

Potatoes were soon playing a major role in Ligurian cuisine, replacing beans and chickpeas in many recipes and definitively canceling out “Greek fava beans,” also known as bacilli, which had been the typical accompaniment for more than three centuries of the stoccafisso (dried cod) eaten on fast days. “There is no family that does not eat dried cod and favas on All Souls’,” according to the saying.

Much of the penitential merit of the dish was lost, no doubt, when stoccafisso in tocchetto (dried cod stewed with tomatoes, mushrooms and anchovies) and cod accompanied by potatoes arrived on the scene.

The potato is also featured in dishes with pasta, the classical trenette and trofiette with pesto, along with green beans, which are also native to the New World.

While Liguria can be described as, historically, the first and most enthusiastic adoptive parent of the potato, it was not the only region to take in this New World foundling. As usual, each local cuisine adopted the potato after its own fashion, creating recipes that reflected an uncommon gift of inventiveness.

In Piedmont, the potato is used in making gnocchi and gnocchetti or cabiette di Rochemolles. It is also boiled, fried, roasted or puréed in dishes that are common to all other areas of Italy as well. In the Trentino, it is made into mushes like polenta, fritters and pinze (a sort of baked potato pancake). In the South Tyrol, potatoes are the basic ingredient of Kartoffeln Krapfen (potato crêpes).

Friuli-Venezia Giulia has its patate in tecia (a stew) and budino dolce di patate (a sweet pudding of potatoes). In the Veneto, the potato is combined with rice, while in Venice potatoes are fried with onions and flavored with parsley (alla veneziana). Emilia-Romagna has come up with a tortino (potato slices baked in a casserole with milk, cheese and butter). The Tuscans employ the potato in preparing a soup.

In addition to being used in making gnocchi, the potato is cut up and fried in tocchetti (pieces) in lard and olive oil in Latium and also used in preparing a special tortino.

In the Abruzzo, the people prefer patate sotto il coppo (an iron cover under which peeled potatoes are baked in the fireplace, buried beneath live coals; the potatoes are usually flavored with olive oil, vinegar and salt). In Apulia, they are used in making focaccia or buns, a special type of pizza and fritelle alla tarantina (fritters). Potatoes are combined with baccalà (dried salted cod) in a tortiera or “cake” in Basilicata.

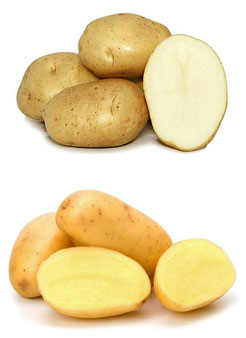

The uses to which potatoes are put in Italian cuisine are so varied and special that close attention must be paid to the correct selection of the appropriate type. Potatoes are divided into two principal groups on the basis of the color of the pulp—yellow and white. Both are excellent and have the same nutritional value.

The yellow pulp is certainly tastier but it is more compact, which makes its amalgamation with other ingredients difficult. Therefore, that type of potato is more often used alone, fried or roasted. For gnocchi, purées and similar dishes, potatoes with a white pulp are preferable.

BACK TO

RuvidaMente

RuvidaMente