Capsicum and chili peppers are believed to have originated in the tropical regions of Central or South America, most probably in what is now Brazil. Uncertainty on that point is due to the fact that both have been widely consumed for thousands of years in extensive areas of the New World.

Pepper seeds have been found in ancient Peruvian tombs, particularly at Arricon in the vicinity of Lima. Other discoveries, along Mexico’s Gulf coast, and historical sources further confirm the fact that peppers were a common food of the Olmec Indians, whose civilization reached its zenith between the 5th and 1st centuries BC.

The discovery of peppers and their subsequent introduction into Europe were, in fact, closely linked to one of the principal objectives of the expedition led by Christopher Columbus: obtaining direct access to spices. As a consequence, he had hardly set foot on the soil of the New World than he was diligently making inquiries about every article that, because of its odor or appearance, appeared to be suited to a condimental role.

It was on Haiti that Columbus concluded that he had found a new type of pepper. “Theirs [the Indians’] is of finer quality than ours and no one eats a dish without seasoning it with this spice, which is highly beneficial to health,” he wrote. “On this island alone, 50 caravels of this article could be loaded every year.”

The peppers that were introduced into Europe, like the other solanaceous plants, including the tomato and the potato (all related to the nightshade family), were fully domesticated and had been cultivated for centuries. They were, therefore, substantially developed in comparison with the original wild species. They readily adapted to conditions in European countries as on other continents, including North America, where they were introduced from Europe.

The ease with which they could be grown promoted their rapid diffusion. By the end of the 19th and beginning of the present century, botanists were listing nearly 300 varieties. For new varieties, growers relied on spontaneous development of hybrids until the first half of this century when genetic selection was begun on a scientific basis, a process that is still under way on both sides of the Atlantic. The result has been a drastic reduction in the number of varieties, although new types are constantly being developed by botanists. In any case, there has been a substantial improvement in the quality of varieties cultivated.

Contrary to what might be assumed from the rapid and extensive diffusion of peppers, the plants’ culinary history has been far from illustrious. They shared the fate of the other solanaceous plants, which were quickly adopted as food sources by poor country people, who were usually the first to take up novel articles of diet from other continents.

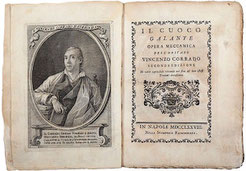

Vincenzo Corrado, a native of Apulia who was a noted gourmet-writer of the 18th century, remarked in the 1781 edition of his Il Cuoco Galante that “although peppers are a rustic food of the masses, there are many who like them…they are eaten when they are green, being fried and sprinkled with salt or cooked over the coals and flavored with salt and oil.” They are still prepared in the second fashion in many parts of Italy.

Corrado’s comment was virtually the sole reference to peppers between the 15th and 18th centuries. There is not even an entry for peperone in the ponderous dictionary of the Accademia della Crusca.

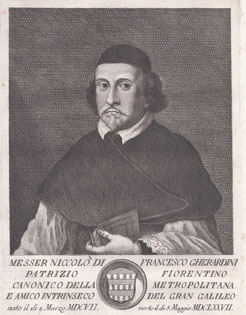

It was litterateur Giovanni Gherardini (1778-1861), annoyed at finding defects in that dictionary, who was the first to describe the pepper, as follows: “A tube or conical berry, with a tough skin that is a fine red or yellow in its maturity and bright green when it is immature.”

In respect to its culinary qualities, he observed that it had “a piquant flavor almost like [black] pepper’s. Peppers are eaten raw, basted with oil. But, in addition, they are preserved in vinegar and are called peperoni acconciatti or conci.”

In traditional Italian cooking, peppers have received much more attention in the south, although there are some delicious preparations in northern cuisine, like the Piedmontese peppers stuffed with rice.

Among the traditional recipes, mention should be made of the stuffed and pan-fried peppers of Latium as well as that region’s classic preparation in which peppers are combined with chicken.

The peppers with baccalà (dried salt cod), imbottiti (stuffed with olives, capers, garlic and anchovies) or in teglia (peppers cooked in oil and flavored with garlic, anchovies, capers and tomato sauce) of Campania are delicious, as are the involtini di peperoni (roasted peppers filled with capers, anchovies, pine nuts, raisins and breadcrumbs and baked), stuffed peppers and peperoni soffritti (fried in oil with scrambled eggs) of Apulia.

Calabria is noted for its peperoni ammollicati (fried in oil and sprinkled with breadcrumbs, grated pecorino cheese, capers and oregano) and alla calabrese (stewed in oil and flavored with tomato concentrate), while Sicily excels with roasted peppers and peperonata alla siciliana, a dish similar to ratatouille.

Hot peppers are more frequently used as a spice than as a basic ingredient. Everyone is familiar with the tasty pasta formula of garlic, oil and red pepper. There are numerous other uses for the spice, like aromatizing oils, vinegars and grappas, as well as fermented cheeses like bruss .

Peppers can be divided into two types: sweet and piquant.

Sweet peppers, in turn, can be divided into four major categories depending on their shape: peperone quadrato, which is boxy in shape; peperone a cuore di bue, which in shape resembles a top; peperone a pomodoro, which is small and highly compressed, and peperone a corno, which is thin and elongated and either straight or curved.

Among the peperoni quadrati, the best-known types are those of Asti, Nocera and the meraviglia of California.

Among the peperoni a corno, mention should be made of the corno di Spagna, also known as the corno di toro (bull’s horn).

THE FIRST ITALIAN RECIPES

Again, Vincenzo Corrado took the lead in providing the first “official” Italian recipes for peppers. In the process, he showed how extremely varied and imaginative were the ways in which Italian cooks were using peppers.

Peperoni alla Pastetta, Vincenzo Corrado, 1781:

When the peppers have boiled, divide them in half and fry them after dipping them in a batter of white wine, oil, flour and salt. Serve them hot.

Peperoni alla Purea di Ceci, Vincenzo Corrado, 1781:

Grill the peppers over charcoal, clean away the burned skin and remove the seeds. Fry the peppers in oil with garlic and parsley. When they have cooked, serve them with puréed chickpeas.

Peperoni alla Ramolata,

Vincenzo Corrado, 1781:

Boil the peppers in water and remove the skin and seeds. The peppers are served with a salsa ramolata [rémoulade] consisting of anchovies, parsley, marjoram, garlic, oregano and finely chopped lemon peel and oil and vinegar.

Peperoni Ripieni, Vincenzo Corrado, 1781:

The peppers can also be stuffed. First, however, they must be grilled over charcoal to remove the skin. The stuffing consists of anchovies, parsley, garlic, olives and oregano, all finely chopped, and stewed in oil and flavored with pepper and salt. They are baked in the oven or cooked on the grill on oiled paper.

BACK TO

RuvidaMente

RuvidaMente