The introduction of the New World’s zucche and zucchini created less of a stir in Europe than other types of unfamiliar vegetables from the Americas, because some of their relatives had already been cultivated and regularly consumed in Europe for centuries. However, the newcomers were more attractive and much tastier.

Both the “old” and the “new” vegetables belong to the gourd family (Cucurbitaceae). Most if not all of the Old World varieties belong to the genus Lagenaria and are true gourds. They originated in India and were brought to Europe in remote ages before the rise of the Roman Empire. Europeans ate the pulp of some species, while they dried others and used them as containers. The varieties of the genus Cucurbita were taken to Europe from the New World and are now grown and consumed throughout the continent.

The scientific nomenclature may be admirably precise but there is much confusion in the vernacular. In Italian, for example, the word zucca is used to refer to both gourds and to pumpkins and similar squashes.

However, gourds are meant when the word zucca appears in documents that predate the introduction of squashes into Italian cuisine.

Today, zucca usually means pumpkin and other squashes, although the word can properly be used when gourds are intended. Squashes, principally zucchini, are usually called marrows in Britain.

In the United States, squash is the term widely used for members of the Cucurbita group, except for gourds and cucumbers. It is derived from the Natick and Narraganset Indians’ word for the vegetables, askútasquash.

However, Americans have adopted the Italian word zucchini in reference to the green squash in recent years.

It should be noted, however, that the exact origin of the pumpkin and some other squashes is much disputed. Some experts say Europe acquired them millennia ago from an Asian homeland, while others insist that they originated in the New World. If they did evolve in Asia, they were transplanted to the Americas at an early date, perhaps around the same time they spread to Europe.

The ancient Romans were certainly familiar with the gourd, although they did not hold it in much esteem. It was regarded as a food of the poor and Virgil observed that the “lowly gourd rested heavily on the stomach.”

In cuisine, the gourd was appreciated for its versatility, although it may not have been as adaptable as the stingy

Caecilius thought. According to Martial, in No. XXXI, Book XI, of his Epigrams,

Caecilius “is a very Atreus [who cut up the children of Thyestes and served them to their father at dinner] to gourds…he so mangles them and cuts them into a thousand pieces….Gourds you will eat

at once, even among the hors d’oeuvre.

Gourds he will bring you at the first or second course. These in the third course he will set again before you. Out of these he will furnish later on your dessert. Out of these the baker makes insipid cakes, and out of these he constructs sweets of all shapes…mincemeats, so that you believe lentils and favas are set before you; he imitates mushrooms and black-puddings, and tuna’s tail, and tiny sprats.”

Apicius gave nine recipes for gourds in which the vegetables were boiled, fried or stuffed. However, gourmets were not really keen on gourds. They preferred the young shoots, which were cooked and eaten like asparagus.

Pumpkin and zucchini only entered Italian cuisine after the seeds of Cucurbitaceae were brought to Europe from the New World and the plants began to be cultivated in Italian gardens. In the 16th century, Sienese botanist Pietro Andrea Mattioli observed, in discussing the cooking of pumpkin, that “it is the practice to eat it either boiled or fried in the pan or roasted. Boiled, it has little appeal in itself. When roasted…or fried in the pan, it releases a great deal of its moisture. Nonetheless, because of its natural water, it should be eaten with oregano.”

In his Economia del Cittadino in Villa, published in 1644, Vicenzo Tanara talks about “white or long squashes, called cucuzze in Rome,” which, because they require “a lot of sun and a great deal of water, are not much consumed in our area [Emilia].In Rome, these white cucuzze are forced to grow to an unusual length and to remain thin by having pots of water placed under them. They are attracted by the water and grow toward it, stretching out in the process. Once they have been peeled, the cuccuze are cut in slices, fried in oil and served with lemon juice.

Or they are fried in fat or butter. They can also be hollowed out and stuffed with whatever you wish or with provatura [a

cheese made from buffalo milk], then boiled or stewed and served.”

Tanara notes that there are two types of squashes, those with yellow and those with white rinds. He adds that the type with a yellow rind was more widely consumed. He devotes

a great deal of attention to ways of preparing “extremely tender zucchettini along with zucca.” Among the ways he suggested are boiling the squash or cooking them in the ashes under

the coals of a fire, in which case they should be flavored with rose vinegar, oil, salt and pepper. Or they can be dredged in flour and fried or stuffed with a mixture of bread, pine nuts,

raisins, greens, verjuice [a wine made from immature grapes], cooked must or ricotta cheese, grated cheese, raisins and eggs.

His treatment of pumpkin and similar squashes is also exhaustive. He reminds the lady of the house that, “as soon as the plants begin to run along the ground, they can be used in cooking. The tips of the initial shoots must be trimmed off so that the plant will develop more branches and fruit. Those tips, boiled and served in salad with pepper sprinkled over, are delicious and even more so if you combine with them a bit of very tender zucchettino. Squash can be cooked in many ways but it should be noted that, being moist and insipid, they must necessarily be fried and accompanied, whether da magro che da grasso [without or with meat or some extract of it], with other warm, savory things. It is sometimes cooked in milk or whey or it is fried to remove the moisture. For soups, squash are cleaned, cut into chunks and boiled in good fatty broth and pounded in the mortar with leftovers. from past meals. They are served with eggs and covered with cheese. Cooked, and with the moisture pressed out, they are made into pies accompanied with grated cheese, ricotta cheese, eggs and pepper. In whatever way they are prepared, they must be accompanied by some other thing. Otherwise, they are neither good nor healthy. They can be regarded as symbols of hope deluded, since you believe they are highly nutritious when you see their plump shapes. But they offer nothing or little in themselves and that little grows out of the accompanying foods, which also provide flavor.”

“On fast days, the most tender squashes can be boiled or wrapped in paper and cooked over the coals.

They are served in slices with rose vinegar, oil, pepper and salt or they can be cut in slices, salted, dredged in flour and fried.

The slices are served with verjuice and, on days free of fasting, with fat and butter, in which way they are healthier because they give up their water. If you want to use them to make a non-meat soup, cook and purée them and bind the mixture with almond or pine nut milk.

But, best of all, is the ‘milk’ of their seeds, which is better in binding rice and similar foods.

“Peeled tender squashes are emptied of their marrow and filled with a stuffing made with bread, pine nuts, raisins, greens, verjuice, spices and cooked must. Or they can be filled with the pounded flesh of fish with a bit of finely chopped dried tarantello [tuna preserved in oil] blended with raisins and spices. In addition, squashes can be stuffed with small balls of pounded pike with the livers and spleen of the same fish, or with herring, tartuffi di mare [the warty Venus clam], prawn tails, preserved Genoa capers and similar items. For feast days, the squashes are filled with chicken livers and giblets, veal sweetbreads and pounded thin veal or capon meat. The largest, after being boiled, can be stuffed with small birds, squabs or boned poultry combined with slices of ham or mortadella or with one or the other pounded. Finally, they can be filled with an ordinary stuffing of ricotta cheese, grated cheese, raisins, eggs and similar articles, while some people stuff them with hard-boiled eggs. Squashes can be cut into small pieces and mixed with onions, chopped parsley, oil, verjuice and pepper, then stewed in a pan or pot."

“The long white squashes known as cucuzze in Rome are cut in slices and dried in the sun And they are toasted until they are as hard as rocks. Then, they can be taken anywhere and are very useful for soups and to cover boiled meats accompanied by salamis and sausages. Cut in slices, they are fried in oil and served with lemon juice or fried in fat or butter. In addition, they are hollowed out and filled with any of the stuffings mentioned above that you wish or with fresh buffalo milk cheese, then cooked or stewed and served.”

In virtually the same period, Lodovico Castelvetro (1505-1574) wrote that, “with the end of the hot weather, the long white squashes are ready. They are bigger than the arm of a large man, although not all of them reach that size. If soup is to be made of these, they are boiled in water with salt. And, when they are almost cooked, a substantial quantity of good greens is added along with olive oil and finely chopped small green onions as well as a bowlful of immature grapes, known as agreste.

The smaller squashes, when they are green, are peeled and cut across, not lengthwise, producing round slices as thick as half a finger. After being dredged in flour, they are fried in oil. Once fried, they are sprinkled with salt, pepper and the juice of grapes that are not ripe. Instead of what you might think, the juice of lemon is not to be excluded. The spice sellers cure quantities of the largest squashes in honey and sugar. The squash is then known as zuccato and it is an excellent condiment to have with a wide variety of foods.”

A century later, in the 1700s, zucchini were praised as a food by Vincenzo Corrado, an Apulian by birth but a Neapolitan by adoption, in his treatise Cibo Pitagorico.

The variety of zucchette and zucche lunghe dishes he proposed would challenge the most imaginative of modern cooks: alla campagnola, all’oritana, al torna gusto, in insalata alla italiana, alla Dama, in pottaggio da magro or da grasso, farcite alla nobile (stuffed with breast of pullet and fatty veal, Parmesan cheese, pine nuts and marjoram), farcite alla Paolina (with fish pounded with anchovies, pine nuts, a bit of garlic and greens, cooked in fish stock and served with a purée of shelled beans or chickpeas), alla Monaca and zucchette alla milanese (the squash are filled with rice cooked in broth and flavored with grated cheese, egg yolks and beef marrow; then stewed in broth and served with a coulis of capon or a milk “purée”).

Many of those preparations have survived to the present day and it is not difficult to find them duplicated in recipes of Italian regional cooking.

Such preparations include the Ligurian torta di zucca, minestrone and tortelli, Lombardy’s zucca fritta, the puréd squash and marinated yellow squash of the Veneto, Emilia-Romagna’s cappellaci and tortelli and Sicily’s ficato and sette cannoli.

Zucche have an advantage in Italian cooking in that they have been around much longer than other purely New World foods, for, as already noted, pumpkins and some other squashes may or may not have been known to and consumed by Europeans before the end of the 15th century.

The zucchina (or zucchino, customarily used in the plural, zucchini) was absolutely new to Europe, along with many other squashes. When the New World zucchini came along, they replaced dishes made with zucche, which may have been gourds or squashes and which were harvested while still immature or green.

The substitute was better than the original in this case, since the young zucche were said to be extraordinarily bitter. Recipes created with the New World imports in mind began to appear about the middle of the 17th century. Inhabitants of Piedmont began to eat stuffed zucchini and zucchini alla piemontese. Rice with zucchini became popular in the Veneto, while the Marche took to zucchini that are baked or stuffed with guanciale (cured pork jowl). Marinated zucchini appeared in Latium, while they were used in pasta and soup in Campania, where zucchine in scapece (first fried, then marinated in oil, vinegar, garlic and herbs) also became a popular dish. Apulia developed zucchine alla poveretta or in parmigiana, while Sicilians prepared them in sweet-sour sauce (agrodolce) and Sardinians stuffed them

Italians have not been content to nibble at the tips and the fruit of squashes. They have also used their flowers

(fiori di zucca) to create numerous dishes. The flowers, collected before they have fully opened, are delicate and fragile and they have stimulated the imaginations of generations of cooks,

who have stuffed the blooms with anchovies and mozzarella cheese, dipped them in batter and fried them, added them to omelets and flavored them with Parmesan cheese, parsley and nutmeg.

Most recently, they have been stuffing the blossoms with a delicate chicken mousse.

THE FIRST ITALIAN RECIPES

As already noted, the European zucca, whether a true squash or a gourd, was quickly supplanted by the New World varieties. But it had been a part of the Italian gastronomic tradition, which explains the rapidity with which the newly imported varieties were incorporated in the country’s cuisine. The adoption of the potato and tomato was a much longer process. To illustrate that point, the recipes are given below for two preparations that were described in texts published before the first voyages to the New World. The other dishes represent the early stages of the incorporation of the new varieties in Italian cooking.

Torta di Zucche Secche, anonymous Venetian writer, 14th century.

Boil the squashes [or, more probably, gourds], then pound them with pork fat and put them in a bowl. Add as much cheese, along with pepper and saffron, and blend thoroughly. Bind with eggs and use the mixture to fill a pastry shell.

Zucche Fritte, Maestro Martino, 1450.

Take some zucche and wash them well. Cut them across into slices as thin as a knife blade. Put them to boil in water. As soon as the water boils, remove and dry the slices.

Sprinkle with salt, dredge them in flour and fry them in oil. Take a bit of fennel flowers, garlic and bread with the crust removed. Pound them in the mortar, adding verjuice so that everything will remain moist. Pass the mixture through a sieve and spread it over the zucche.

It would be good to sprinkle some verjuice and fennel flowers over the dish. If you want the sauce to be yellow, add some saffron.

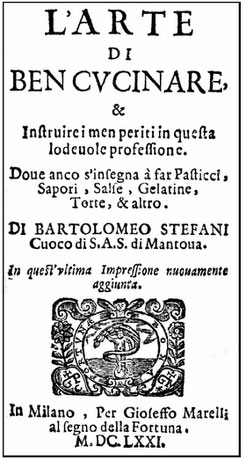

Minestra di Cime di Zucca, Bartolomeo Stefani, 1662.

Take the vine tips of the zucca; if they are those of zucchetti, it would be best to blanche them first in broth. Once blanched, put them in a small pot with capon broth and two cheeses cut in small pieces and previously blanched. Add verjuice that is made three times a year from grapes that are large and have a great deal of pulp and, once the skins have been removed, are crushed, the seeds then being taken out afterward. Put in two ounces of grated Parmesan and two eggs so that the soup will be thickened.

Vivanda di Zucchine, Bartolomeo Stefani, 1662.

Take the zucchino, remove its skin, cut it in slices and macerate and soften them in salt so that they yield their water. Arrange them in layers, one atop the other, and put a weight on them so that they will lose their moisture even better. Carefully dredge them in good flour and put them in a pan in which butter has been melted. Cook them, then remove them from the pan and make the following sauce.

Take a bit of basil, a leaf or two of erba amara [bitter herb, probably garden balsam, the French mélisse] and a few fennel seeds and pound well in the mortar and for every pound of sugar, take four ounces of soft cheese and pound well in the mortar. Moisten the other ingredients [presumably the herbs] with verjuice, but add none if they have previously been moistened with water.

But in case they have not been, add two ounces of sugar with four fresh egg yolks that have been well beaten. Put all the ingredients [apparently the slices of squash] in a pan over the heat with three ounces of butter. Mix the ingredients with a wooden spoon. When you see that the mixture is cooking, cover this dish with the sauce and serve it cold, sprinkled with cinnamon.

If you want to fry the zucche in oil, make the sauce in this way. Instead of cheese, add bread with the crust removed and soaked in verjuice along with the herbs above and in place of the egg yolks use almonds that have been prepared in the same way. When the zucche are more mature, they can be cut in the same shape as lardoons. They can also be stuffed in addition to being used as casings for forcemeat stuffings. Many other dishes can be made from them, enough to provide an entire meal.

Zucchette in Insalata, Vincenzo Corrado, 1781.

Tender zucchini are cooked in salted water, then drained and allowed to cool. Dress them with oil, anchovies, oregano and pepper.

BACK TO

RuvidaMente

RuvidaMente