The turkey is a member of the Meleagridae family of birds and originated in the New World, where it was found throughout the United States as well as on the central plateau of Mexico, in the Yucatan Peninsula and as far to the south as Guatemala.

Two species existed at the time the Europeans first reached the Americas, the common and the ocellated turkey (the ocellated turkey has eye-shaped spots on its feathers).

The Indian peoples were well acquainted with the bird. They consumed its meat and used its feathers as ornaments. There is documentary evidence that the Aztecs raised them and it is probable that other Indian peoples did so as well.

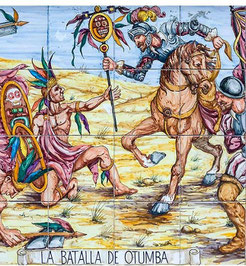

Christopher Columbus made fleeting contact with the turkey along the coast of Honduras on his fourth voyage (1502-1504). However, the bird was only officially discovered during the conquest of Mexico by Hernán Cortés.

“They [the Indians] raise many hens that are like those of the mainland [Europe] and they are as big as peacocks,” the Conquistador wrote in his Cartas y Relaciònes, which were sent to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain, and published at Zaragoza in 1522. However, Cortés provides no information about mole, a dish that is a characteristic feature of Central American cuisine. It is made with turkey and powdered cocoa.

The Spanish immediately learned to appreciate the turkey and imported it to Europe, although it is impossible to determine the exact date.

The first turkeys known to the English appear to have been offered to Henry VII of England at the beginning of the 16th century, while the first birds raised in Europe were served at the marriage of Charles IX of France in 1570.

It seems probable that the birds reached the table of the French king by way of the Jesuit convent in Bourges, where turkeys were first raised on a large scale in Europe.

The priests of the Company of Jesus were largely responsible for establishing the bird’s reputation on the continent and their coq d’Inde (rooster of India) was widely referred to as a jésuite before it became familiarly known as dindon or dinde.

The turkey made what appears to have been its first appearance in art in a still-life painting of the Dutch artist Joachim Beuckelaer (1530/35-1573/74), which is now owned by the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

The “chicken of India” was being raised and consumed in England by at least 1525. Its introduction has been credited to merchants who traded with the Turkish empire and India beyond and who customarily called at Seville on their return journey. It is assumed that the birds were obtained in the Spanish port by the “Turkey merchants,” as they were known. Their merchandise was at first called turkey bird but that was soon shortened to tur key.

The Indians, who knew quite well that the bird was not a native of their country, gave the turkey the name peru, which was closer to the mark than the European names but still off by a continent, since the bird originated in North America.

In Germany, the bird is known as a Calecutischerhahn (Calcutta hen), another example of the enduring fallout from the erroneous conclusion that the lands Columbus “discovered” were part of the Indies. The navigator himself certainly believed until the day he died that he had reached the Far East. The Spanish, who of all people should know the bird’s origin, call it pavo, or peacock. The Italians call the turkey tacchino, which is said to be derived from the French word tache, a stain or spot, because the bird’s feathers are mottled.

It appears that the English were primarily responsible for launching the turkey on its extraordinary culinary career, for they soon adopted it as the traditional main course at Christmas dinner, a role it usurped from the goose. In the United States, of course, it is the main fare at the Thanksgiving Day meal, as well as the year-end holidays.

In Italy, Bartolomeo Scappi included a recipe for “rooster of India” in the second book of his famous recipe collection, Opera dell’Arte del Cucinare, which appeared in 1570.

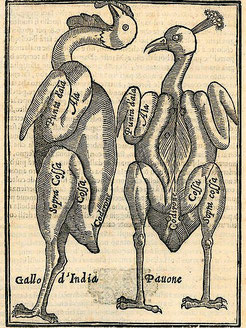

Shortly afterward, Vincenzo Cervio, who was in the service of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, described the turkey in his book Il Trinciante (The Carver), published in 1581, as “this bird large of bone and meat and of the same goodness and prestige as the peacock, for which reason it should be carved in the same way.” And he presented it at a series of banquets of the highest level.

The rooster of India was served up “stuffed with ortolans and covered with large asparagus spears cooked in butter, studded by cinnamon and with stewed truffles” or “covered with cardoons, cervelletti [pork-and-veal sausages] and truffles roasted with capers along with citron.”

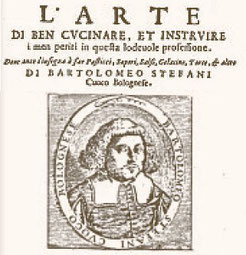

In L’Arte di Ben Cucinare, published in 1662, Bartolomeo Stefani, cook to the Duke of Mantua, suggested a much speedier way of dealing with a turkey in the kitchen.

“Cook those that are smaller and tenderer on the spit, larded, so that they will satisfy every taste.” He also suggested that “those fattened in the months of January and February” should be “cooked Swiss style with wine and studded with cinnamon and mastic.”

A couple of decades later, in 1684, Carlo Nascia, chief cook to Ranuccio II, Duke of Parma, Piacenza and Castro, included about a dozen recipes for the “rooster of India” in his Li Quattro Banchetti Destinati per le Quattro Stagioni dell’Anno. By that time, the turkey, known familiarly by such childish terms as pitto, pittino and papinotto and still formally called tacchinotto rather than the modern tacchino, held a firmly established place in Italian cuisine. One of those formulas was rather special, turkey prepared with Morello cherries.

Nascia also offered his readers a recipe for “turkey flavored with candied fruit” and another “in the form of a pelican.” Among his other suggestions were stuffed turkey, turkey in galantine, in Borgia sauce, roasted with verjuice, with cream and sugar, with herbs and with kidney sauce.

The Indian rooster, whose plumage and the show he made of it were less impressive, eventually chased the gaudier but more aristocratic peacock from pride of place at the great banquets of the mighty. The changeover marked the passing of an epoch and of a particular style of cuisine. However, while his plumage is less showy, the turkey’s meat is less stringy and, above all, the bird is more readily available, with a price that puts it within reach of most people today.

THE FIRST ITALIAN RECIPE

The gastronomic success of the turkey was immediate, facilitated, no doubt, by the poor gastronomic quality of its half-brother that it would replace in our recipe books, the peacock.

Furthermore, the peacock was an animal mainly treated by court chefs or by patrician families, people rich in professionalism and gastronomic culture, accustomed to treating new foods and inventing optimal adaptations of codified techniques.

Only a few centuries later did the turkey free itself from the gastronomic heritage of the peacock and original recipes were created for it, constructed to best enhance the intrinsic characteristics of its meat.

Recipe for the “rooster of India” (Bartolomeo Scappi, 1570)

The rooster and hen of India have much larger bodies than the native peacock. The rooster displays his plumage just as the peacock does and has black and white feathers, a neck of wrinkled skin and at the top of the head a horn of meat that, when the rooster is angry, puffs up and becomes big in such a way that it covers all of the beak. Some others have the said red horn, mixed with a peacock blue-green color, that is as large as the breast and at the point of the breast they have a cluster of spiky feathers similar to the bristles of pigs. The bird has meat that is much whiter and much more tender than that of the peacock and it becomes high much sooner than that of the capon and other, similar poultry.

Should you want to roast it on the spit, do not let it hang after it has been slaughtered with its entrails unremoved for more than four to six days in the winter and for more than two days in the summer. Pluck it dry or after dipping it in hot water, in the same way you pluck a hen. When it has been plucked and its entrails removed, prepare the breast. Since it has a bone that is taller than other birds have, you must cut the skin in a strip along that bone and carefully detach the meat from the said bone and cut the point of the bone with a knife…then sew up the skin.

If you want to stuff the bird, fill it with one of the mixtures mentioned in Chapter II, Section 5. Remove the wings but leave the head and the feet and blanch it in water. When it has blanched, let it cool and…being fat, it need not be larded but deck it out by putting in some cloves. Spit it and cook it slowly. This bird cooks much more quickly than the peacock. With the breast meat, you can make polpette, ballotte and all the dishes that you can make with lean milk-fed veal, as given in Sections 43 and 47; all these you can make from the “hen of India” and from the peacock but immediately after they are dead [without being hung], for if they are high they are not as tasty. The said rooster and hen have the same season as the peacock. It is quite true, however, that they are eaten throughout the year in Rome. Their giblets are prepared in the same ways as those of the peacock as cited above.

BACK TO

RuvidaMente

RuvidaMente