In architecture, as in design and fashion, there is a lot of talk about two opposing trends: the baroque and the understatement. In essence, two contrasting ways of seeing things face each other, the first devoted to the exaltation of external aspects, often an end in themselves and misleading with respect to the function of the object to which they are applied, and the second respectful of the practical purposes for which the object was created, even ready to mortify its aesthetics if any of its pleasantness were to limit its functionality.

Curiously, transferring the terms of this debate to the world of wine, we discover that, in addition to being pertinent, the topic has many surprises in store for us. What changes are the temporal parameters and the absolute non-contemporaneity of the trends.

In its substance, in fact, wine has been for millennia an essential, bare product, one hand highly appreciated for its substance, alcohol, which interacted strongly with the drinker's body, while on the other hand it offered the perceptual system a restricted range of both olfactory and visual stimuli, as well as gustatory stimuli.

NECTAR, RAGWEED AND LIQUOR

It is no coincidence that, scrolling through the pages of the ancient texts in which it is mentioned, the praises always refer only to one of its characteristics, sweetness, which makes it described, from time to time, as nectar, ambrosia or lyre.

Until the threshold of the 20th century, in short, very little was asked of wine: alcohol content and "sweetness". And the copious presence of the two determined the quality.

Despite this structural simplicity, wine has crossed the millennia as a mythical element, overflowing with symbolic values and, for this reason, always at the center of crucial events in history and culture. All this is not due to that mix of sensations, aromas and flavors that send us contemporary tasters into raptures, but only to its alcohol content. Wine has become a myth not for what it was but for what it triggered in those who drank it, that is, for the joy it induced, the drive to socialize, the loosening of inhibitions, and so on until the inebriation and oblivion induced by drunkenness.

THAT IT IS SWEET AND CAPABLE OF INEBRIATING

On the other hand, thanks to the lack of knowledge that has accompanied winemakers for millennia, all efforts have always been aimed at obtaining a wine characterized by the highest possible alcohol content. A factor that, over time, has even become institutionalized, becoming an objective parameter of value (often mistaken for "quality") to which prices, duties, excise duties and taxes are anchored.

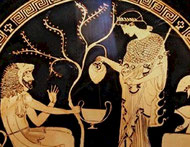

In lack of tools able to modify the substantial profile of the wine, our ancestors indulged in surrounding it with external elements that would still convey its value. So when it was valuable (i.e. rich in alcohol and sugar) they kept it in decorated amphorae, served it by pouring it from finely chiseled jugs, drank it by sipping it from precious cups, sometimes even gold.

From the end of the 1600s onwards, when the first bottles began to circulate, and with them the labels were born, it was all a succession of friezes, frames, flourishes, seals and coats of arms, which only apparently gave a baroque appearance to a product that continued to be, in essence, simple and functional.

Things began to change only at the beginning of the 60s, when viticultural and oenological technique triggered a process of renewal that involved technicians, producers and consumers. The chronicles of the first isolated chronicler of those times, Luigi Veronelli, begin to account for something other than fullness, power and sweetness: aromas and flavors are isolated, they are compared, the whole is evaluated by introducing the categories of harmony and balance. Starting from those years, and for the first time in its history, wine began to be judged for the sensations it can give while drinking it, instead of after drinking it.

AND THE TIME OF EMOTIONS CAME

As this new sensibility spreads, there is an irrepressible acceleration of research and producers find themselves at their disposal, in the vineyard as well as in the cellar, of very sophisticated knowledge and tools that allow them to bend such a "difficult" material to their will, to shape it according to a pre-established project, to obtain "the wine they have in mind". It is a sort of Copernican revolution, a magical moment in which those who make wine almost have the feeling of being omnipotent and are pushed to launch into projects unimaginable only a few decades earlier. It is as if stonemasons had suddenly found themselves in the hands of laser chisels with which they could intervene at will on stones and metals. Here they are, therefore, intent on operating, first in the vineyard and then in the cellar, to manage the development of polyphenols, acidity levels, sugar concentration, tannin balance, aroma spectrum, color intensity.

The most striking results of this new trend can be found today in the great red wines, true concentrates of sensations, opulent and complex, brilliant to the eye and redundant to the nose and palate, powerful but at the same time elegant, rich but with a richness that shamelessly overflows into the superfluous. In short, baroque.

THE ETERNAL STRUGGLE BETWEEN FORM AND SUBSTANC

Faced with this explosion of the Baroque, once again, the one who is taken aback is the consumer, who is not ready to perceive such a wealth of sensations.

Let's think about it. If two equally short-sighted people, one equipped with glasses and one without, enter a Romanesque church, both have the opportunity to enjoy the architectural preciousness of that structure, poor in decorations and rich in elements that are both formal and structural.

If the same two people enter a Baroque church, the one without glasses will be condemned to a decidedly more miserable sensory experience, unable as it is to perceive the thousand subtleties that enrich every detail, the overabundance of decorations that cloaks both the formal and structural elements.

Today's consumer of quality wines is more or less in the situation of the short-sighted in a baroque church: he has so much to perceive but lacks glasses. Fortunately, he understood this and it is no coincidence that, never as in these times, the sommelier courses and the many others organized around Italy are stormed by enthusiasts of all ages. And this gives us good hope for the future.

BACK TO

RuvidaMente

RuvidaMente